Etnofutu – The Ethnofuturism of Fashion

The fashions of a thousand years ago

What's in here?

This specific page gives a short look into the clothes of the Northeastern European cultural region that Finland was, among others, a part of. There is a subpage for the concrete ethnofuturism, where these things turn into living cultural heritage.

Notice: if the regions and ethnicities referred to are confusing, see some maps.

MATERIALS

The bottom layer was likely made of linen and nettle. Neither of them survive the centuries particularly well, though, so there isn't any prehistoric data. Similarly underwear in the strict sense is largely guesswork – likely close to known Mediterranean styles of the Antiquity, where breasts were wrapped with a bandage-like long strip of cloth, and bottoms could perhaps most accurately be called loincloths. Trunks-like underwear is also a possibility: 19th century Siberians wore that kind of things.

The top layers were made of wool, and in some occasions leather. Iron Age sheep still had a double fur, and they had stiff, strong outer hair in addition to the soft wool we are so familiar with. (Ryder 1981.) Cloth made from the wool of primitive sheep was much stronger than modern wool cloth, and was used for example in sailmaking. (Cooke et al. 2002: 203.) The wool of modern, plush-toy-like sheep is adulterated with synthetic fibers mostly because the eternal drive for softer wool has ruined the wool's capacity to withstand shearing and pulling stress.

Linen and nettle and naturally a sort of khaki tone. They can be bleached, but not permanently dyed without modern chemical methods. Linen clothes were consequently quite light. Primitive sheep, on the other hand, were as a rule dark – gray, brown or even black rather than the white now common. (Ryder 1981.) Wool can also be bleached, and then also actually dyed. Common colours were blue and red, (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2001: 13–14.) which as dilited concentrations yield a sort of aquamarine and terra cotta. Most likely the price range of woollen clothes from cheapest to most expensive was something like dark–white–faded–vibrant. Clothes in general were so labour-intensive and consequently expensive, that the poor most likely had one of each item. (Jarva & Lipkin 2012.) Woollen clothes were decorated with bronze at least as early as the 9th century. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 241.)

BELTS

The most common type of belt preserved and found in inhumation graves is a lather belt decorated with metal elements that the leather is ran through. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 248.) A subset of this is the helavyö, in which more metal elements hang from the ones attached to the belt itself. Some graves feature the tools and items hung from a belt, but no surviving belt. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 247.) These are likely to be woollen cloth belts familiar to us from the 19th century, although realized as tablet-woven bands in the contemporary style rather than the inkle-woven, more modern types.

The helavyö was originally a women's belt in the Upper Volga, but more to the west – and in the western islands of Estonia and the western coast of Finland even today – it was used as a men's belt. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 246.)

UNDERWEAR

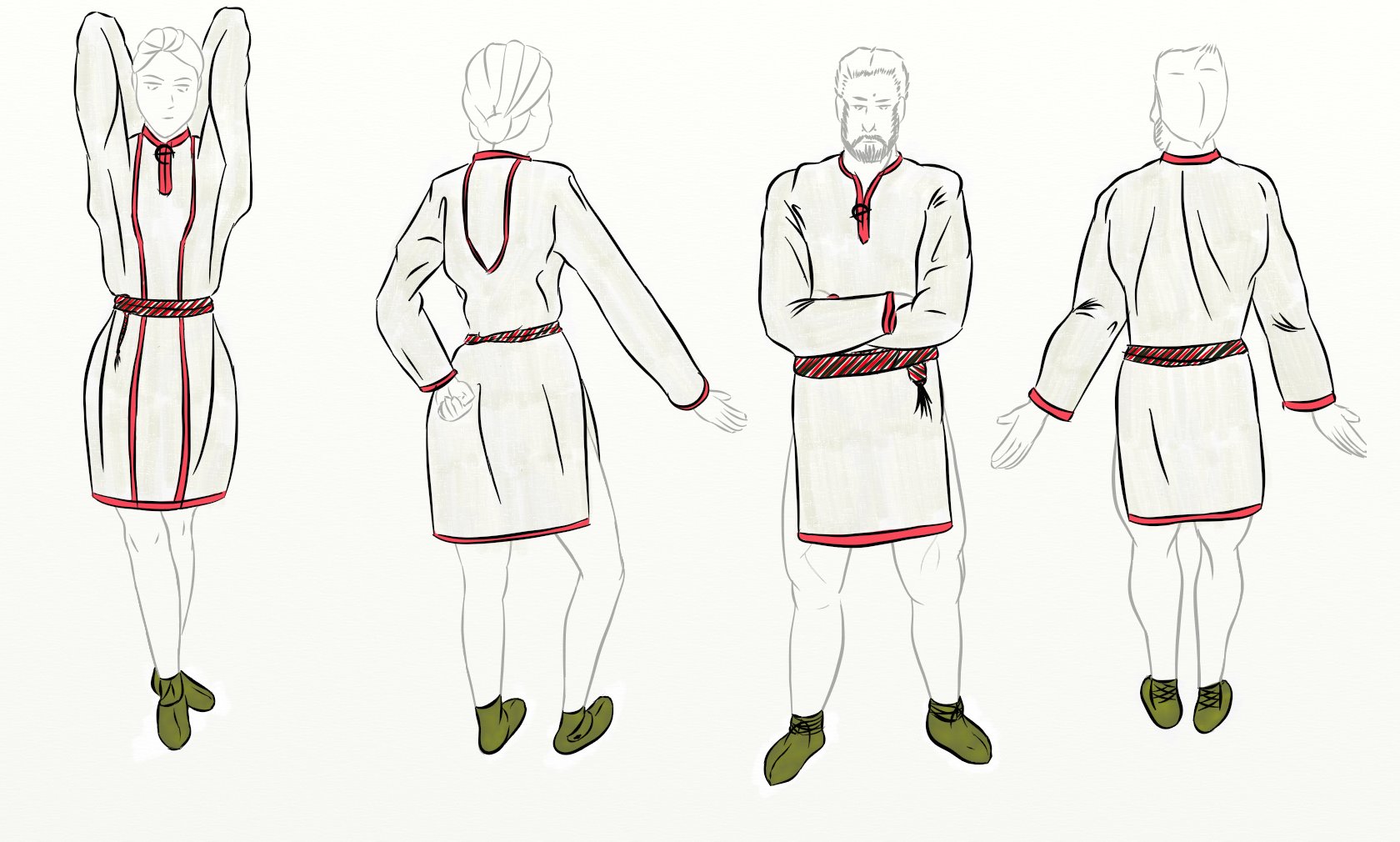

SHIRTS

Shirts for men and women were very similar in their construction – their differences were mainly in the respective decorations. That is – is the 19th century, as prehistoric linenwear really doesn't survive. The parts that have survived are woollen decorations – tablet bands sewn onto the cloth or embroidery. In some cases the woollen decoration survives around brooches or other bronze elements, shielded by the toxicity of the bronze breaking up. The cut of the ancient shirts is left open, and is here, as has been previous work, based on 19th century styles of the more eastern Uralic groups. Modern data from the cemetary of Siksälä in Southeastern Estonia supports this: especially well preserved items prove a hypotesis from the 1920's that Finnic groups decorated the backs of women's shirts as did those in the Volga basin. (Laul & Valk 2007: 59.)

The decoration of a man's shirt is minimalistic: the cuffs of the sleeves, the collar and the hem are capped with wool. 19th century Mari men also had decoration running over their backs. (Manninen 1929: 224–225.) Women were, as they are, more lavishly decorated – stripes ran down from the collar to the hem or away down the sleeves. Stripes or loops were found on their backs. (Manninen 1929: 175, 224–225; Laul & Valk 2007: 57.) Some of the decorative bands are found where clothes are damaged the most, like the cuffs. The bands were fairly easy to switch out, and well may have had a functional purpose as well. So how common were the bands? That is unclear. All clothes were supposed to be decorated in the 19th century, but photographic evidence proves that this wasn't exactly universal. Prehistoric finds in Scandinavia feature plain clothes, but then a caved-in salt mine slave from the 3rd century A.D. in Dürrnberg did have bands on his sleeves. (Knudsen & Grömer 2012.)

There are two possibilities to the cut of the shirt: either as in Scandinavia wedges would start immediately below the sleeve structure, giving shirts a sort of dress-like quality, or as in the Volga basin there could have been vents at the sides, leaving panels hanging to the front and the back. Without intact specimens this is left in the air, and both might have well been used. The dress-like structure would be more warm, but the vents look better to me at least. The illustrations feature both. The sleeves were straight and attached to the trunk with square panels, widening the entrance of the sleeve. The hem would ran down to mid-thigh or just above the knee, with the shirt worn over trousers and the collar closed with a brooch. (Laul & Valk 2007: 59; Lehtosalo-Hilander 2001: 27.) In the Volga basin brooches were were used into the Middle Ages. (Lehtinen 1999: 23.) It is likely that collars were raised already in the Iron Age, but is no direct evidence before the 19th century.

On the left vertical bands from the collar to the hem with a sleeve-length loop on the back. Vents in the three rightmost illustrations.

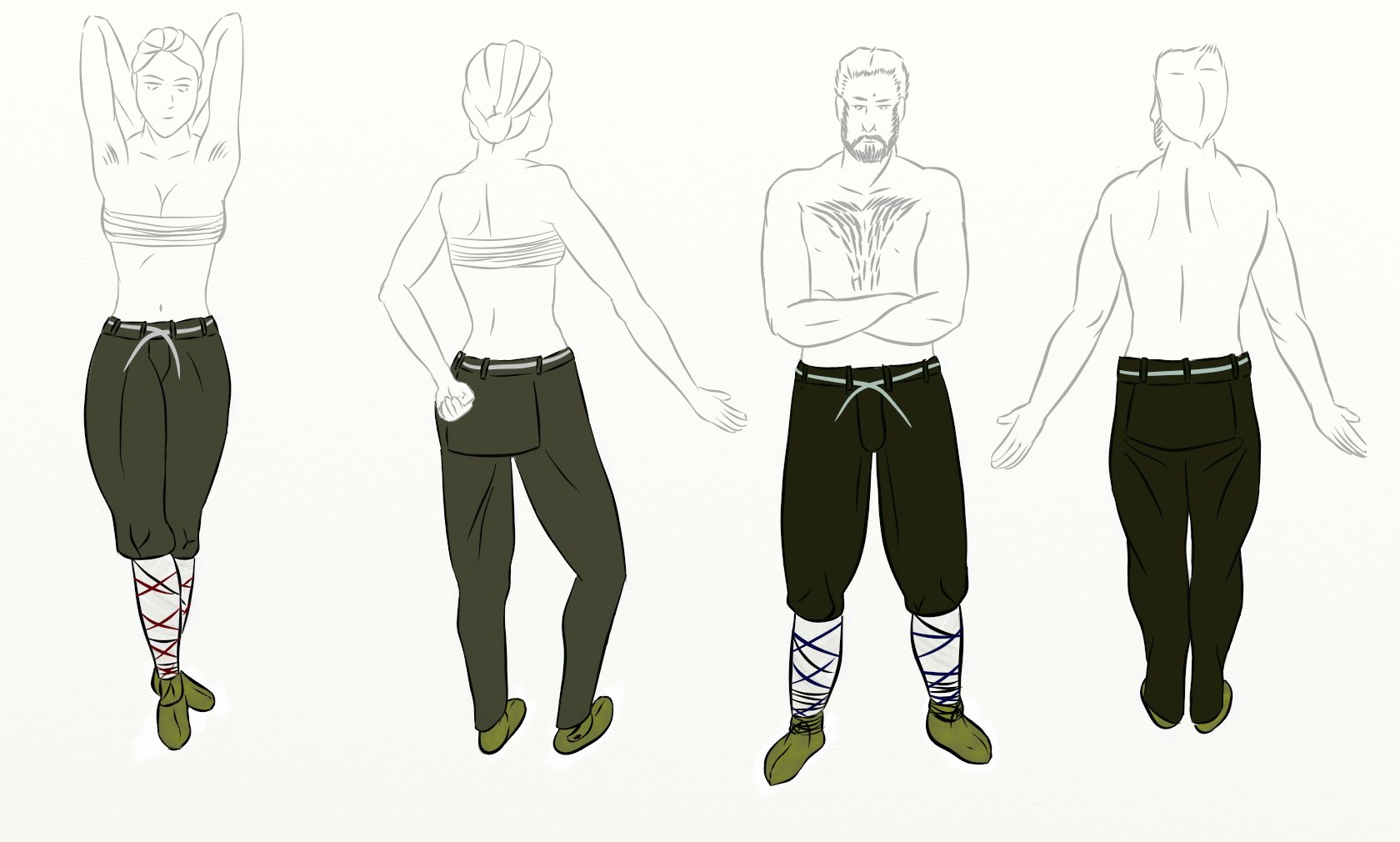

TROUSERS AND LEGWEAR

There are no surviving trousers from Finnic areas, so we have to operate on indirect evidence. Trousers have certainly been used, since tablet bands used to tie gaiters have been found. In Livonia in modern Latvia this also applies to women. (Mägi & Ratas 2003: 213.) This necessitates visible trousers, as the bronze shin decoration would not be hidden under a long skirt, and it seems unlikely that oily, rough promitive wool would have been worn against the skin. The women of the Mari and Morvins, who persisted in their native religion the longest, wore trousers even into the 20th century. (Mägi & Ratas 2003: 213.)

The trousers have a panel structure, with large pieces in the front and the back, to which the legs are attached. The structure leaved the wearer with a lot of room to move in, and unlike modern fashions they allow the wearer to squat and climb freely. In addition, there's no seam in the middle, which I imagine to be quite nice on a horse or sitting on hard surfaces. Scandinavia has surviving specimens and carved depictions of both trousers tight in the shins and almost dress trouser-like wider models. The wide trousers are depicted in nautical scenes, so they may be a way to avoid getting sea spray onto the shins, as in wide sailor trousers of later times.

The shoes were likely leather ankle booth. Without surviving examples from Finland or Estonia I have drawn Scandinavian models. There are no signs of the knee boots fashionable in the 19th century, and prestige footwear was instead gaiters with bronze decorations. We can tell that the gaiters were a footrag type because of the way they were attached – Scandinavian puttee-like gaiters were tied to the top with special clasps, entirely missing from burials. The footrag types are instead tied with bands, that have been found. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 254.) My own leg can be comfortably enveloped in a strip 1½ metres long, and women's gaiters in the 19th century Volga basin were up to 3 metres long. (Manninen 1929: 182, Lehtinen 1999: 20.) A thick, wrapped up shin was seen as beautiful, and there's a certain similar look to Permian bronze jewelry from the 8th and 9th centuries A.D., depicting local goddesses. The fertility goddess typified a strong and healthy woman with a thin waist and powerful limbs. (Autio 2001: 175.) Perhaps, then, an ideal lady for the Iron Age Finns could be found in an amateur weightlifting competition?

On the left tight trousers closely correspoding to the bog trousers from Thorsbjerg with and without gaiters. On the right a wider, sailorlike model.

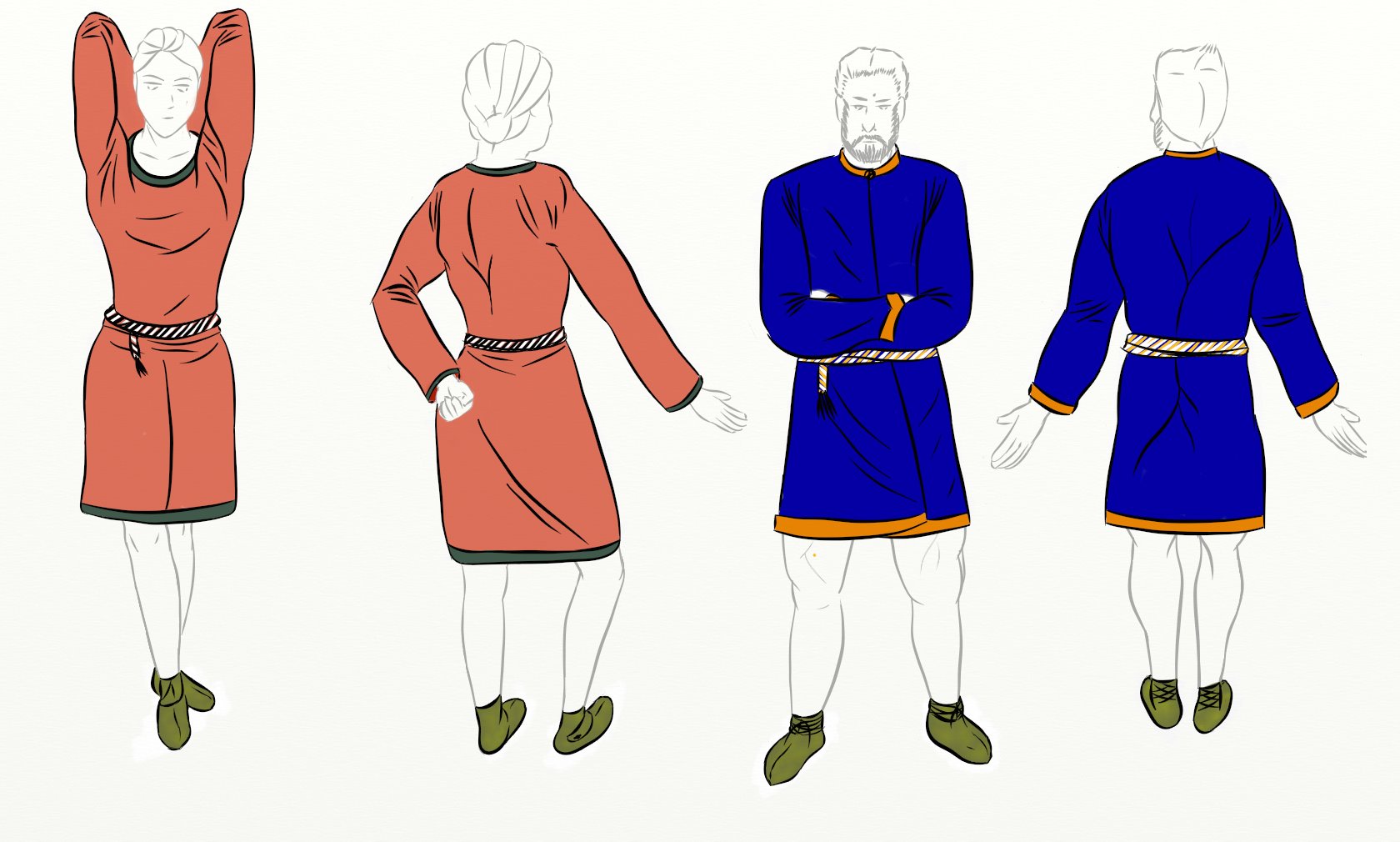

Overwear

COATS

Coats have two clear models: one open and one closed. The closed model was particularly popular in Estonia. (Mägi & Ratas 2003: 219.) A model that opens up in the middle seems to have been more popular – they were closed with a belt and a brooch (Appelgren-Kivalo 1907: 57.) or in some cases buttons made out of jingle bells. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 253.) Buttons as a concept exist as early as the Stone Age, but even then their main function was decorational, and closing clothes with them, as we do, was at best a secondary function. Men and women had different bells: women's bells had a softer, jingling sound, while the sheet metal bells of men and horses made more of a clanking sound. (Raitio 2006.) The sound of bells gave the higher social classes an air of their own, a concept not all that distant from our lives – the crack of iron heels thundered militarism in Europe within living memory, and still does in Russia.

Coats are also found in women's graves, but much less frequently. (Laul & Valk 2007: 59.) Much like with shirts, coats for men and women seem to have been quite similar apart from their decoration. Some leather jackets of a similar cut to woollen ones have been found in Estonian burials. (Laul & Valk 2007: 59.) Leather jackets are likely to have been used everywhere, as animals would be butchered, but it seems they didn't have the prestigious air demanded of burial dress. Perhaps leather and fur clothes were seen as something for only utilitarian use.

Unbuttoned, knee-length coats were worn in 19th century Eastern Finland, and they likely corresponded fairly well to Iron Age designs. (Kaukonen 1985: 197.) In the east Russian-style ankle-length coats had replaced the older models in menswear, but women still favoured the knee-length cut. Udmurts had the opening in the middle, but the Mari, perhaps as a Russian influence, had it on the left breast. (Lehtinen 1999: 41.) It is, however, possible that the opening off to the side was used earlier – one burial features a brooch on the side, but it may have found its way there during the centuries after the burial.

On the left a closed coat, on the left one open in the middle. The closed model by necessity has a wider neck and a looser cut.

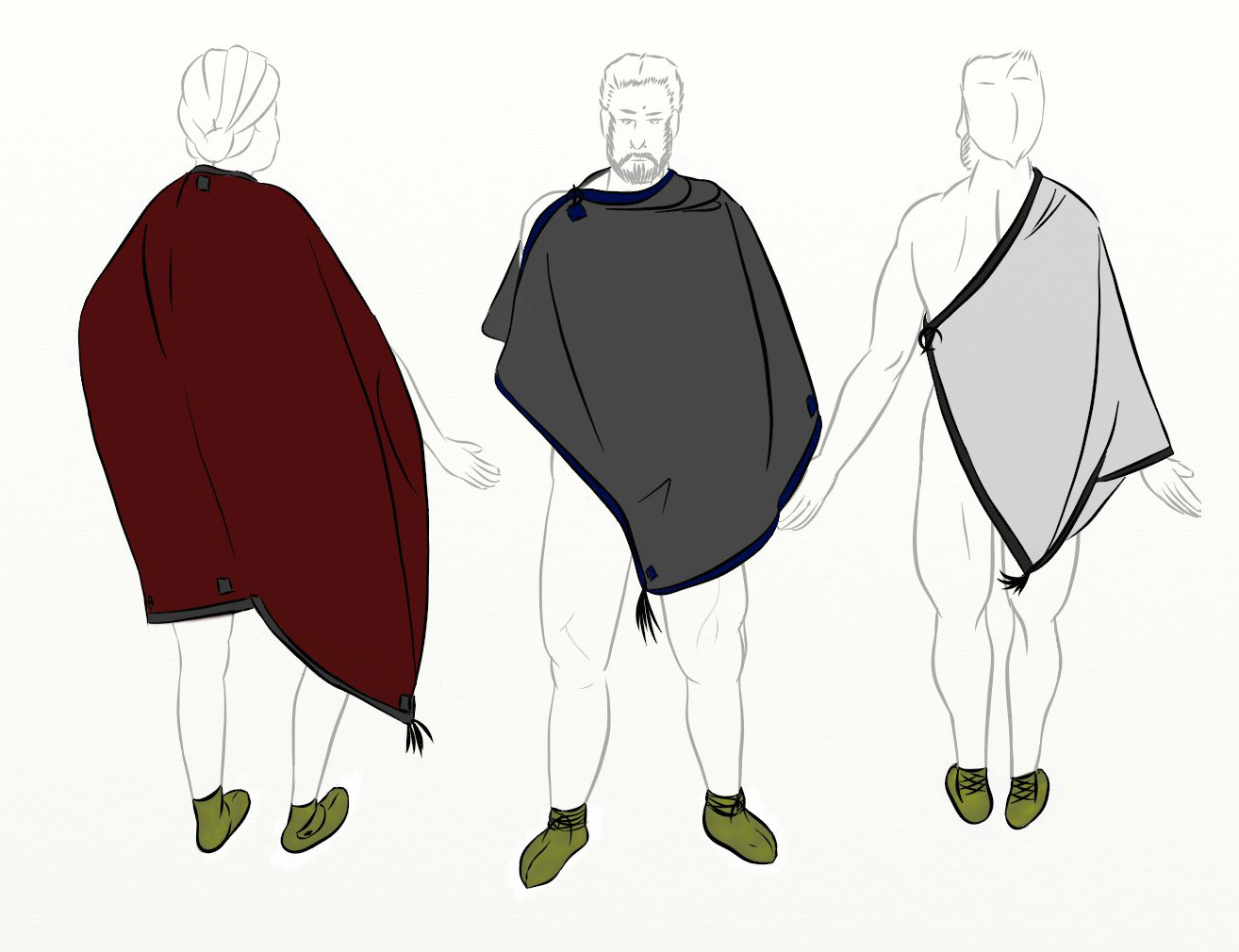

CLOAKS

Cloaks for men and women were broadly the same: rectangles of cloth, decorated at the edges. (Laul & Valk 2007: 51–56.) Their size, however, varied strongly region to region – the smallest, Votic shoulder-scarves in Ingria, were barely larger than modern scarves. At their largest, the cloak could extend from the neck almost to the ground. Smaller cloaks were mostly good for protecting the neck, while the larger ones were likely used as sleeping bags and raincoats in addition to dandying around town. Women's cloaks were, again, more richly decorated. (Appelgren-Kivalo 1907: 45.)

The way to attach a woman's cloak would be familiar to us today: the long edge to the neck and the rest hanging down symmetrically, with a brooch at the chest. If necessary, the ends can be gathered up to allow use of the hands. For men, two methods are attested in burials: sideways with the brooch either at the shoulder or under the arm, of which the latter seems a more modern style. (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2000: 248; Lehtosalo-Hilander 2001: 81.) The brooch at the shoulder gives a poncho-like impression, and is much more warm and utilitarian. The brooch under the arm gives a regal, toga-like appearance, but the arms is cold no matter what. It seems likely that the older style would have been used while actually doing something, with the new fashion relegated to looking good.

Cloaks for women had notably more bronze decorations, for example in the form of decorative squares the the edges and corners of the cloak. Cloaks went out of fashion for men during the Middle Ages, but women wore them just as before as late as the 16th century in Livonia. (Laul & Valk 2007: 49.)

In a certain sense hoods can be thought of as cloaks – tight, woollen winter hoods with flaps extending down to the sternum from Iron Age Scandinavia are effectively identical to linen mosquito hoods in 19th century Eastern Finland and Komi. It's likely that they were used over here in the east as well. I've used a mosquito hood in fieldwork, and it works surprisingly well. The mosquitoes keep away from the face almost as well as with a modern mosquito net, and it doesn't impede your breath the way nets do.

Medium cloaks: from the left a woman's style, followed by the older and newer style for men.

JERKINS

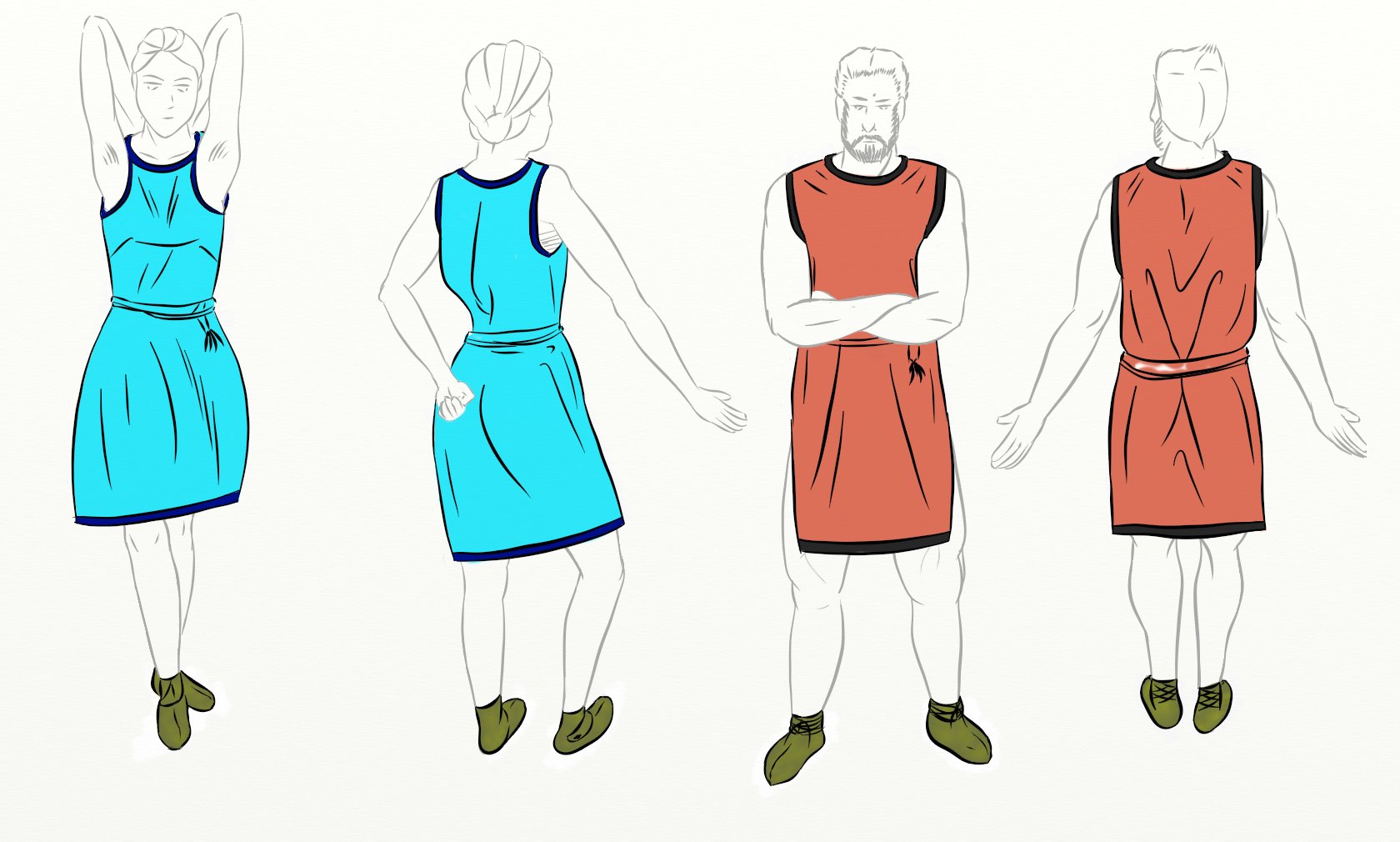

Sleeveless jackets resembling very longs vests were used as womenswear in Karelia and menswear in Udmurtia in the 19th century. (Manninen 1929: 50, 248.) In Estonia they were used by both genders as late as the Early Modern period. (Mägi & Ratas 2003: 212.) Burials attest to woollen overclothing, that is not long-sleeved (Lehtosalo-Hilander 2001: 79–80.) – material survives is such sporadic amounts that the sleeves could have terminated anywhere between the shoulder and the elbow. These items could be a short-sleevel coat as in Scandinavia, but a sleeveless model seems more likely in the light of more modern data.

Sleeveless overwear has been surprisingly popular throughout history, and sleeveless winter jackets exist even now. At first glance this seems like a fairly useless thing to wear, but linen clothes flap uncomfortably coldly in the wind even at a +10 degrees centigrade, but only in the stomach and thighs. The arms and shins stay surprisingly warm. Jerkins may have, in this light, been a windbreaking spring and fall item, that could when necessary be combined with a cloak.

A closed model on the left, one with vents on the right.

A closed model on the left, one with vents on the right.

APRONS

Aprons were decorated within living memory in Lapland. Embroidering an item that will inevitably get dirty seems odd to modern eyes, but towels have been decorated throughout history as well. In part an apron is a sign of ritual purity in addition to a functional item. There exist more elaborate variations on the theme: 19th century Votes in Ingria and Muromians around modern Moscow in the Middle Ages wore a cloth folded in half over the belt. (Manninen 1929: 104–105.) Estonians and Mordvins used two aprons at once – one in the front and one at the back. (Mägi & Ratas 2003: 216; Männinen 1929: 174–175.) Votes and Mordvins also used something called koittana's, long decorative panels running down from the belt at the rear sides. (Manninen 1929: 93–94, 174–175.) Izhorians, also in Ingria, went as far as using a skirt with integral elements giving the impression of double aprons. (Manninen 1929: 96–97, 104.)

A plain apron on the left, an Izhorian in full kit with a skirt and koittana's on the right.

A plain apron on the left, an Izhorian in full kit with a skirt and koittana's on the right.

PEPLOS

An item similar to the peplos of Antiquity is found in late Iron Age burials on the coast of the Gulf of Finland, likely as a Scandinavian influence. (Laul & Valk 2007: 79; Mägi & Ratas 2003: 212.) Like a cloak, this is a large rectangle, attached to the shoulders with oval brooches and belted at the waist. One side is left open, and a long underdress was worn with them. This isn't a part of the larger Northeastern European style shown above, but is something that did exist in Iron Age Finland.

The Peplos was worm with a breastful of dangling metal (not pictured), and they were likely used solely as formalwear.

WHOLE COSTUMES

On the left: Leather snkle boots, gaiters of linen, dark woollen trousers, a tablet-woven belt, a linen shirt and a blue woollen coat. The vibrant colours of the coat show this older gentleman to be quite wealthy, but he is either not quite swimming in money or is not above working in these clothes.

On the right: Leather ankle boots, gaiters of linen, dark woollen trousers, a jerkin in terra cotta, a metal helavyö, and a dark cloak. The combination of natural and light colours, but not without bronze pieces, shows that this young lady is not badly off. The belt and very small cloak are a combination of Upper Volgan and Ingrian styles, and might have been seen together near what would become Novgorod.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Appelgren-Kivalo, H. (1907) Suomalaisia pukuja: myöhemmältä rautakaudelta. Helsinki: Tilgmann.

Autio, E. (2001) The Permian Animal Style. Folklore Vol. 18&19: 162–186.

Cooke, B. et al. (2002) Viking woollen square-sails and fabric cover factor. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2002) 31.2: 202–210.

Jarva, E. & Lipkin, S. (2012) Ancient textiles were expensive. How do you know that? The XII Nordic Theoretical Archaeology Group.

Knudsen, L. & Grömer, K. (2012) Discovery of a new tablet weaving technique from the Iron Age. Archaeological Textiles Review No. 54: 92–97.

Laul, S. & Valk, H. (2007) Siksälä : a community at the frontiers : Iron Age and Medieval. Tartu: University of Tartu/Högskolan på Gotland.

Lehtinen, I. (1999) Marien mekot : volgansuomalaisten kansanpukujen muutoksista. Helsinki: Suomalais-ugrilainen seura.

Lehtosalo-Hilander, P.-L. (2000) Kalastajista kauppanaisiin : Euran esihistoria. Eura: Euran kunta.

Lehtosalo-Hilander, P.-L. (2001) Euran puku ja muut muinaisvaatteet. Eura: Euran Muinaispukutoimikunta.

Manninen, I. (1929) Suomensukuiset kansat: kuvauksia esineellisen kulttuurin alalta. Porvoo: WSOY.

Mägi, M. (2003) Eesti aastal 1200. Tallinna: Argo.

Rainio, R. (2006) Jingle bells, bells and bell pendants – listening to Iron Age Finland. ICTM Study Group on Folk Musical Instruments. Proceedings from the 16th International Meeting.

Ryder, M. (1981) A survey of European primitive breeds of sheep. Ann. Génét. Sél. anim., 1981, 13 (4): 381–418.